Signs to Bridge Two Worlds

Hinsdale South’s Deaf and Hard of Hearing program is a place to be seen in a sound-based world

By Maureen Callahan

Everyone wants to belong and feel accepted. This need is especially acute during the high school years. LaGrange Area Department of Special Education, (LADSE), in collaboration with Hinsdale South High School (HSHS), takes these needs seriously.

The Deaf Education Program offers a state-of-the-art education option for deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) students from far and wide.

The LADSE classrooms are located on the lower level of HSHS.

“Our heart and soul is Hinsdale,” said Director Carrie Morfoot, “but our daily operations are LADSE.” While the DHH Program began as a district program in 1966, it now exists as a co-operative effort between LADSE and HSHS.

“In other words, all program funding comes through LADSE, which rents the space from District 86. “It’s really a wonderful collaboration with the district,” Morfoot feels. “We’re very lucky.”

Currently, 40 students from zip codes throughout the DuPage and West Cook County area are enrolled in the DHH Program. Transportation is arranged through bus service provided by students’ home districts.

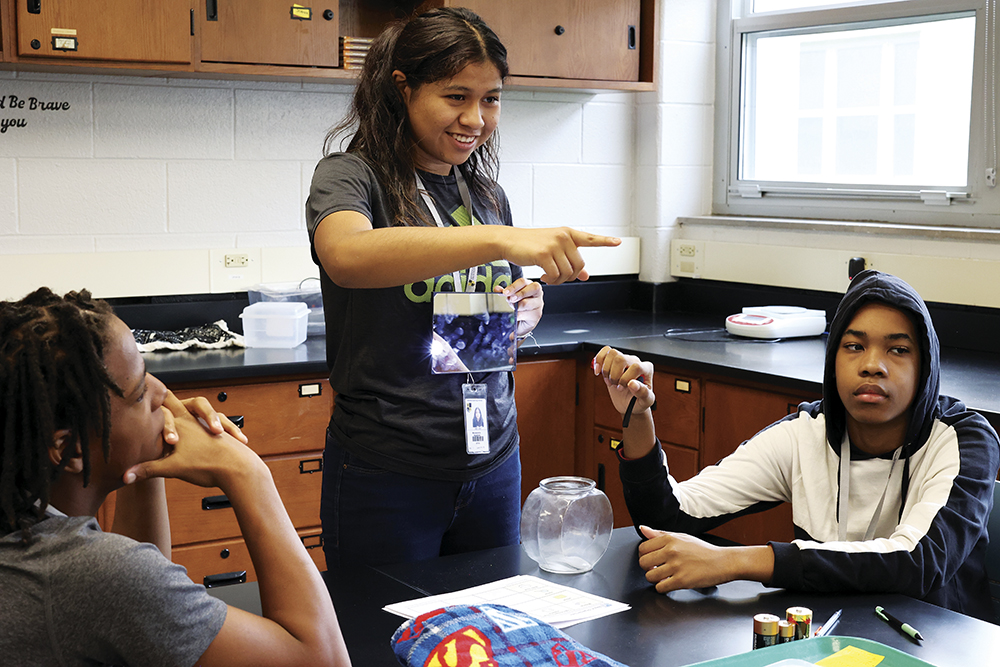

LADSE meets students where they are the day they arrive, providing academics at their level. Varied learning opportunities ensure that all students – from DHH students who are fully mainstreamed with interpreter services to students with additional disabilities – have the tools they need to succeed.

“We have a lot of success with our students because we are able to provide them with a lot of individual attention,” said Morfoot.

Students come into the program at all academic levels. They work in co-operatives, similar to a cohort system, grouped with students of similar ability. Teachers present to classes using total communication, which is American Sign Language (ASL) paired with speech.

Many students are mainstreamed, learning in a regular classroom alongside their hearing peers while accessing the classroom environment through sign language interpreters. A staff of interpreters is always available to attend classes with these students, as well as extracurricular activities.

A total communication approach of ASL, accompanied by speech, are used.

“Often, teenagers don’t want to stop the teacher and admit they’ve missed something,” said Morfoot. “We advocate for them to tell their teacher they’ve missed something or let their interpreter know so they can get help,” said Morfoot.

Students with disabilities, in addition to DHH, can spend much of their day in a community-based classroom learning life skills, such as cooking and laundry, in addition to academics. They also hold jobs around the school that offer a chance to work with mainstream students, such as lunch delivery.

The DHH program also offers both applied and academic level classes. Applied level courses use academic content and relate it to real-life applications. Academic courses follow mainstream content while providing additional support.

“The goal is always to move students to the mainstream classes whenever possible, but we never want any student to feel overwhelmed,” Morfoot noted. “Sometimes, a student will move into mainstream classes one step at a time. This program offers them a bridge.”

Besides a staff of DHH certified teachers, students have a strong support system of adults, twelve of whom are Deaf themselves. A speech pathologist works with students on communication challenges.

A Deaf social worker helps students work out regular high school issues, as well as providing support for students and their hearing family members. Students who need them are also entitled to services of occupational and physical therapy as well as vision and mobility.

This network gives DHH students a safe space to belong, and be heard. The program provides a means for DHH students to be with others who understand them. Social opportunities via DHH extracurricular activities get students together to have fun outside of school.

American Sign Language (ASL) is offered as a foreign language elective for hearing students. To visit this classroom is to walk into a silent class of students being taught sign language by a Deaf teacher. Students were preparing for a test the following day through various interactive activities.

“My grandfather is hard of hearing,” said ASL student, Mayra Biga. “I would rather teach him some signs to communicate than have people yelling at him. People who know ASL are the minority, but it’s no different than learning French or Spanish.”

“I study ASL because my niece is hard-of-hearing and I want to be able to communicate with her,” said Leen Kanakri.

Teacher Rebecca Wasilewski signed a sentence which the interpreter translated as, “I don’t make this an easy class because I want students to study hard and learn as much as they can to be able to communicate with the Deaf.”

Many ASL students work with others in the DHH program as peer buddies for Deaf students in gym classes, ASL Club or Best Buddies (an international movement dedicated to ending isolation of students with disabilities). One former ASL student has returned as a teacher in the DHH program.

The high school years present challenges at any school. LADSE’s DHH Program works to minimize these barriers for its students and help them prepare to go as far as possible in the world. ■