How faith and advocacy helped a Hinsdale doctor cross to the other side of grief

By Anna Hughes

Dr. Lanny Wilson has delivered over 6,000 babies during his career.

Growing up, Dr. Lanny F. Wilson admired two groups of people in his small, Roman Catholic Kentucky hometown: priests and physicians. He felt his life would be fulfilled if he could become one of the two.

“I liked girls too much to become a priest,” Wilson joked.

So, he pursued an alternative ministry: medicine, with a specialty in obstetrics and gynecology.

“[ObGyn] really fit me like a glove,” Wilson said. “It was a happy specialty … and I love the delivery room, so it was a good fit.”

The Northwestern alum has delivered over 6,000 babies during his 40-plus-year career as a Hinsdale-area physician. Each birth was equally special, and Wilson took pride in the weight of his role during these life-changing moments.

“People would thank me for being there for the delivery,” Wilson said. “I would say, ‘What an honor and a privilege; thank you for letting me participate.’ I never failed to see it as a miracle.”

Wilson wanted his delivery room to have the comforting feel of being at home with the safety and support of being at a hospital. He was always there with encouragement, a hand to squeeze, or a prayer.

“I would gather the family, anyone who is there for the delivery or who was waiting in the waiting room (if they wanted to come in),” Wilson said. “Mom and her spouse would be there holding the baby, and we’d [all] hold hands and we’d say a prayer of thanks after the birth. So, sometimes people would remember that prayer almost more than they’d remember the birth experience.”

Most days after work, he’d leave one family and come home to his own: his beloved wife Linnea and their three kids. That wasn’t the case on Wednesday, March 2, 1994. He came home from a day teaching to find the house empty.

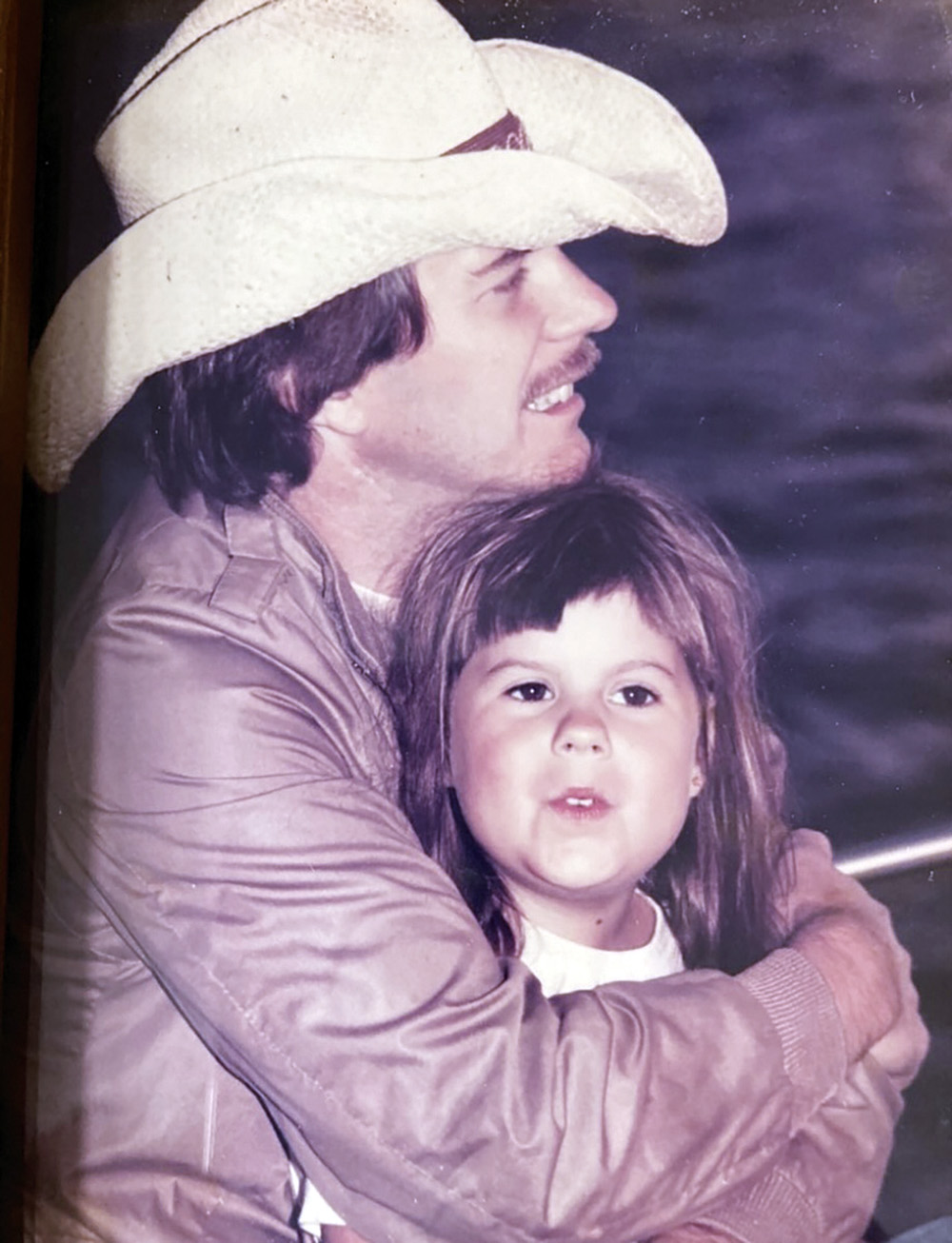

That’s when he got a call that his 14-year-old daughter Lauren and 17-year-old son Luke had been in a car-train accident at the Monroe Street crossing in Hinsdale. They were in critical condition at Loyola University Hospital. Luke remained in the intensive care unit with substantial injuries and later recovered. Lauren died that night.

Wilson, who was so accustomed to the joy of welcoming new life, had to grapple with the end of Lauren’s.

“When our parents die … usually before us, they take part of the past with them. But when our children die, they take part of the future with them,” Wilson said. “So, our world changed. Our futures changed and took a trajectory that we never expected.”

Despite his grief, Wilson knew he had patients relying on him. He was back performing surgery just a few days later.

“Patients would say, ‘Dr Wilson, what can I do for you?’” Wilson recalled. “And I’d say, ‘What you can do for me is let me take care of you. By letting me take care of you, you take care of me. Because this is what I know how to do best.’”

Around the same time, county leaders and first responders noticed an increase in railroad crossing-related deaths and injuries, and they decided something needed to be done. In late April of the same year, DuPage County Board Chair Aldo Botti asked Wilson to lead the newly formed DuPage County Railroad Safety Task Force.

“It was pretty brave of them,” Wilson said of this request. “Here I am, I’m a suffering father. To have that kind of trust that I would lead this group in the right direction and try to be as neutral and fair as possible was a big trust. And I took it seriously.”

He thought about the offer. He thought about Lauren.

She loved the theater and playing piano. She was a good student and could’ve gone on to study politics. She was caring, and she gave great hugs: hugs he missed then and ones he still misses now. He thought about the wedding he dreamed she’d have at their beloved church, Redeemer Lutheran. He thought about his own grief, his wife’s, his two sons’. He thought about how he hoped and prayed that no other parent would have to grapple with the same pain – pain that persists more than 30 years later. He decided this could be a new mission that would complement his continued ministry.

“Bad things happen in our lives, and you can’t go back and change them. What you can change is how you react to them and what you do going forward. [You can] use the energy to try to make the world a better place, in my case, try to make the world a safer place, especially around the railroad tracks,” Wilson said.

Wilson has been the chairman of what is now the DuPage Railroad Safety Council ever since. In their 30 years of operation, they’ve made massive strides in DuPage County, across the state, and even nationwide. They’ve promoted prevention programs, worked closely with the railroad and train companies to engineer safer crossings, and lobbied politicians to work alongside them in implementing life-changing policies. Today, there are 50% fewer deaths and crashes at railroad crossings than the day Lauren died.

“I feel like I’ve been part of something larger,” Wilson said.

After decades of tireless advocacy, Wilson said he’s achieved his goal of making the Monroe Street crossing one of the safest in the world. It’s a tribute to his lifelong goal of helping others. It’s a continuation of the promise he made as a physician to protect and save lives. It’s proof of a lived faith and dedication to ministry that any priest from his small hometown would commend. But most importantly, it’s a testament to the unconditional love that a father has for his daughter.

For more information about the DuPage Railroad Safety Council and the work they’re doing both in Illinois and nationwide, visit dupagerailsafety.org.

Dr. Lanny Wilson and Lauren in the mid-1980s

Lauren Wilson was the president of

her freshman class at Hinsdale Central High School.